The construction sector has made significant strides in workplace safety in recent years, with the HSE reporting in 2022 a 16.7 per cent drop in on-site fatalities compared to the five-year average.

But there’s a hidden epidemic in construction – one that’s controversially not reported in HSE statistics. Even as fewer people die in workplace accidents in construction, the suicide rate has relentlessly continued climbing.

Since 2015, Glasgow Caledonian University and the Lighthouse Construction Industry Charity have compiled figures on suicides in construction. Their latest analysis found the suicide rate for construction occupations in 2021 rose to 33.82 per 100,000 from 25.52 per 100,000 in 2015 – the highest rate in any sector.

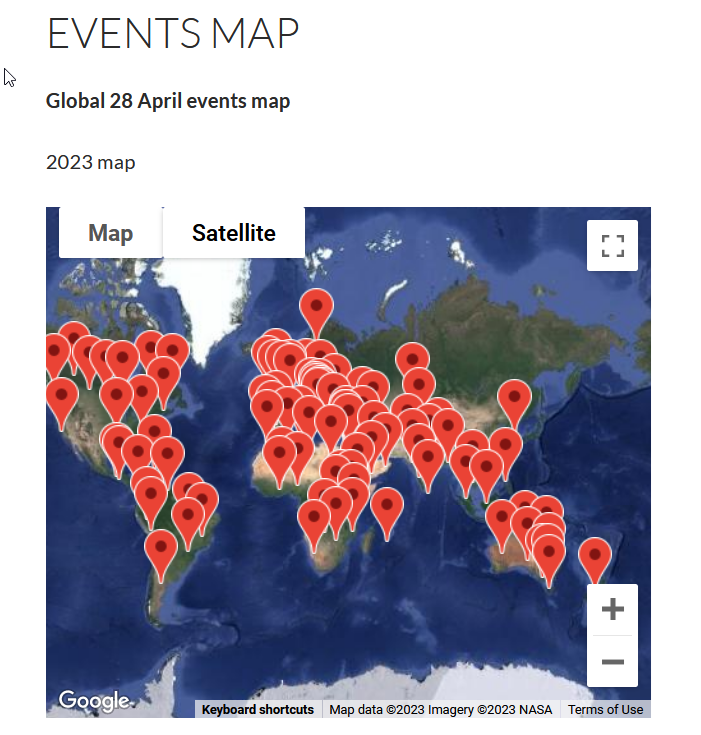

These latest figures were published just two weeks before International Workers’ Memorial Day today (April 28) and serve as a stark reminder that workplace health and safety is so much more than simply preventing accidents in the workplace.

Suicide in the construction sector is both a protracted and complex problem – there’s no one reason that more people take their lives in construction than in any other sector, explains Unite national officer Jason Poulter.

“For starters, it’s a very long-hours culture, and construction workers are often expected to be away from home – and so away from their families and usual support networks – for long periods of time,” Jason noted.

Construction is still a predominantly male working environment, and with this environment comes many of the coping mechanisms that some men turn to in times of stress, such as gambling, alcohol and substance addiction, which often end up exacerbating already poor mental health.

“There is definitely a drinking culture in construction,” Jason told UniteLive. “There’s having a drink, then there’s having a drink — going down the pub with your mates can be a positive thing, but it can just as easily spiral into addiction for some if they’re already under a lot of stress.”

Hinkley Point nuclear power station in Somerset – the UK’s largest construction project since the Second World War, employing more than 4,000 people – was an exemplar of mental ill health plaguing the construction sector in the first few years that the project began.

Back in 2019, Unite told the Guardian that in the first four months of that year alone, the union had been informed of at least 10 suicide attempts by workers employed on the site. Since then, Unite and EDF, the major employer at Hinkley Point, have worked together to redouble their efforts to support workers’ mental health.

Unite convenor at Hinkley Point Malcolm Davies in particular hailed EDF’s mental health buddies system, which is a network of volunteers who are trained as mental health first aiders to provide support and guidance to their colleagues.

“We now have over 400 trained mental health first aiders on site, the most we’ve ever had – with more and more people coming forward to take part,” he explained.

Malcolm believes that what has made the programme so successful is that it has slowly but surely changed the culture at the construction site by removing the stigma associated with talking about mental health.

“People find comfort in talking about their mental health, especially when they can talk to their peers,” Malcolm said. “Our mental health first aiders are often the first port of call and can signpost people to the different types of support they can get. We also have an on-site chaplains, as well as an on-site surgery with nurses and doctors if people need professional, medical help.”

Unite rep Matthew, 27, trained as a mental health first aider at Hinkley Point just a few months ago, and said it’s been a very rewarding experience so far.

“I myself have suffered from anxiety and depression, and I also have family who have been through some tough times, so when I started to feel better, I really wanted to help others who’ve had the same experience as me and pass on what I’ve learned,” he explained.

Matthew noted while the mental health buddies system has been in place for many years, he said a vital difference now is that they’re a lot more visible.

“There’s hundreds more of us, and initially mental health first aiders were more office-based, but now we’re on the ground, dotted around throughout the site. We’ve got ‘time to talk’ rooms where we can sit and talk to people privately. Sometimes people just need someone to listen, other times we can offer guidance like suggesting time off from work, or signposting them to seek professional help.”

Unite rep Anthony, 56, will soon train to become a mental health first aider. Like Matthew, Anthony said he’s keen to help others “because mental health is something that’s close to my heart”.

“I’ve got a little lad who’s severely autistic, and when he was first diagnosed, I went through a really rough period of depression for about a year,” he explained. “I’d like to pass on my experience to others, and sit and talk to people, because that’s what I myself needed to get through the tough times.”

Anthony said he already informally mentors many of the younger workers on site and he can’t wait to be fully trained up as a mental health first aider.

“I’m 56 and when I was a young lad, you just kept things to yourself because otherwise you’d be classed as a softy if you talked about mental health and tried to get help,” he noted. “I think it’s absolutely great now that the lads are so much more open and will come and talk. We’ve got a signs all over the site here that say, ‘It’s okay not to be okay’ and I think that’s fantastic.”

Matthew believes that working conditions in construction definitely contribute to the mental health crisis many in the industry face.

“There’s a lot of long hours, weekend work, and working away from home that I think plays a big role,” Matthew explained. “You end up missing time with your kids, with your partner and parents and all sorts in your social life. You might be home one weekend, but the weekend before maybe there was a party and you just feel like you keep missing out on life.”

While Malcolm said he’s very proud of the mental health work both the employer and Unite have done at Hinkley Point – the union also offers separate mental health training for members – he worries that not all in the sector have access to that level of support.

“On large construction projects, especially in nuclear and petrochemical, there’s a lot more money for mental health projects, and for health and safety in general,” he said.

“I think it’s up to unions like Unite to make sure we’ve got reps on the smaller projects, and make sure we get those reps trained up on mental health. We’ve lost on average 100 people each year to suicide in construction – even one is too many, and it can’t continue.”

Jason Poulter likewise said Unite and other unions have a much bigger role to play to tackle the mental health crisis facing workers in the construction sector.

But he emphasised that it is absolutely vital that employers look at the root cause of this crisis and not simply treat the symptoms – symptoms that in many ways the employers themselves are responsible for.

“There’s needs to be root and branch reform of the employment models used in construction,” he said. “Requisite rest periods – they’re not happening. They’re not paying holidays. They’re not encouraging people to take time off. There’s no work-related mental health risk assessments that we absolutely need.

“There’s also the issue of bogus self-employment where workers are burdened with tax returns and having to pay for accountants, without any of the benefits of working for yourself,” he added. “Because the reality is you aren’t working for yourself – you’re under the instruction of someone else and they can fire you on the spot. They’ve blacklisted workers; they have a culture of fire and rehire – it’s the most precarious industry in the entire economy.”

Jason said that it is not until all these factors are addressed that meaningful change will happen.

“This is what Unite is fighting for day in and day out,” he said. “For every suicide in construction, how many broken families are left behind? This is a much wider problem than many people realise, and we’ve got to do something about it. Too many people’s lives depend on it.”