Each year on this date, labor unions, other advocacy groups and family members mark Workers Memorial Day in recognition of lives lost on the job. In 2019, the most recent year for which data is available, 5,333 workers died of traumatic injury or sudden illness. It’s as if the entire population of Dayton, Kentucky, were erased.

This Workers Memorial Day has a different timbre than previous ones, which have tended to focus on explosions, transportation accidents, falls, trench collapses and other easily measurable events, as opposed to chronic, work-related diseases, which develop over time and take an estimated 95,000 lives a year.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added a fearsome, invisible layer of risk to all of this. And the government agency responsible for workplace health and safety enforcement, which turns 50 today, is under pressure to do something about it.

Since COVID invaded the United States 15 months ago, advocates have urged the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to adopt an emergency temporary standard that would force employers to take steps to quell the spread of the virus, or face penalties. Such standards, intended to address “grave danger,” are exceedingly rare; OSHA has put out nine over the past half-century, none since 1983.

On Monday, an OSHA spokeswoman said the agency had sent a draft standard to the White House Office of Management and Budget for review. It’s unclear how long the review will take, or what will happen as a result.

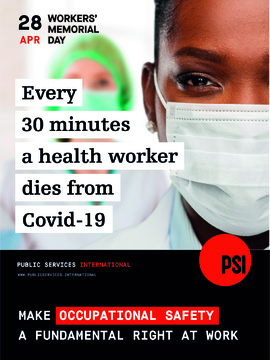

During the Trump administration, OSHA declined to act aggressively on COVID, insisting that non-binding employer guidance – even in high-risk industries such as health care and meatpacking – was enough. That decision has come under heavy criticism. While the total number of deaths across all industries isn’t known, at least 3,758 health care workers had died of the virus as of April 23, according to National Nurses United, a union with more than 170,000 members.

One of them was Celia Yap-Banago, 69, a registered nurse in Kansas City, Missouri, who succumbed on April 21, 2020. She’d fallen ill about a month earlier but had assured her husband and two sons she would make a full recovery. She died in isolation at her home. “We never really thought she would be one of the statistics,” said her eldest son, Jhulan. “Our outlook was, ‘We’ve just got to bite the bullet and wait this one out.’”

On January 21, one day after he was inaugurated, President Biden issued an executive order instructing OSHA to decide by March 15 whether to mandate mask-wearing and other measures on an emergency basis. That deadline came and went. In an email to the Center for Public Integrity, agency spokeswoman Denisha Braxton wrote, “OSHA has been working diligently on its proposal and has taken the appropriate time to work with its science-agency partners, economic agencies, and others in the U.S. government to get this proposed emergency standard right.”

OSHA’s leader during the Obama administration, David Michaels, has argued for the move since the beginning of the pandemic. “There has never been a hazard more deserving of an emergency temporary standard,” said Michaels, a public health professor at George Washington University.

That sentiment is shared by the AFL-CIO’s director of occupational safety and health, Rebecca Reindel, who fears there’s a false belief that the virus has been vanquished, with about a quarter of Americans fully vaccinated and 40% having had their first of two shots. “We’re now in a fourth surge,” she said. “We have variants wreaking havoc in some cities, and we know we’re not out of the woods.”

National Nurses United, an AFL-CIO affiliate, says an emergency standard would force hospitals and other employers to stop cutting corners. A recent NNU survey of more than 9,200 registered nurses nationwide found, among other things, that 81% of respondents reported being forced to re-use personal protective equipment and 47% believed their hospitals were short-staffed.

Pascaline Muhindura, one of Yap-Banago’s fellow nurses at Research Medical Center in Kansas City, told a House subcommittee in March that the lack of an OSHA standard and faulty guidance by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were creating needless peril. “Over the course of the past year, every single nurse and health care worker in my unit has contracted COVID-19,” Muhindura testified. The hospital’s owner, HCA Healthcare, “has failed to provide the N95 respirators and other workplace protections that my colleagues and I needed to do our jobs safely,” she said.

In a statement to Public Integrity, HCA Healthcare spokeswoman Christine Hamele wrote, “Our frontline caregivers have shown unwavering commitment throughout the pandemic, and we have followed or exceeded CDC guidance to protect them. This includes universal protections requiring all staff in all areas to wear masks, including N95s … While labor unions continue to attack hospitals across the country, we remain focused on protecting our colleagues and caring for our communities.”

At the same March hearing, Manesh K. Rath, a lawyer who represents companies and trade groups in occupational safety and health cases, argued against an emergency temporary standard, saying employers had made “a variety of interventions” to slow transmission of COVID and didn’t need the government to tell them what to do. Emergency standards are “immutable and ill-adapted to evolving conditions,” he said, citing a rule issued by California, which runs its own workplace safety program, that was “hastily approved” and had to be clarified several times.

The state regulatory agency, known as Cal/OSHA, makes no apologies for such adjustments. The standard “will continue to evolve to address changes in the availability of vaccines and public health guidance from the CDC and the [California Department of Public Health],” Cal/OSHA spokeswoman Erika Monterroza wrote in an email. As of April 5, she wrote, the agency had cited companies for 503 COVID-related violations and proposed penalties of more than $4.6 million. (Cal/OSHA’s chief, Douglas Parker, has been nominated by Biden to lead federal OSHA.)

Federal OSHA, whose inspection force was gutted by Trump, has citedsome employers using standards governing respiratory protection, recordkeeping and illness-and-injury reporting, and under the so-called general duty clause of the Occupational Safety and Health Act, a catchall that requires employers to provide workplaces “free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm.” As ofJanuary 14, the agency had issued citations after 315 workplace inspections for the virus and proposed penalties of more than $4 million, according to a recent report by the Congressional Research Service.

If OSHA were to issue an emergency temporary standard, it would take effect immediately after publication in the Federal Register and last for six months, after which the agency would be expected to propose a permanent standard. Court challenges by industry, however, would seem inevitable and have proven effective. Of the nine emergency standards issued since 1971, two were vacated in part or in whole after judicial review and three were stayed, the Congressional Research Service reported.

Whatever OSHA does will come too late for Celia Yap-Banago and thousands of other fallen workers. Jhulan Banago, 29, remembers his mother as someone who would initially appear shy but relished her work and “loved to get in people’s business.” Born and trained as a nurse in the Philippines, she had lived in Kansas City since the early 1980s. When she got sick last year, she was pondering retirement – not too seriously, Jhulan believes – so she could travel with her already-retired husband, Amado.

Her symptoms started with a slight fever. Fatigue, a higher fever and breathing difficulties followed. She never felt the need to be hospitalized, however, and was tended to at home by her family. Jhulan found her unresponsive in her bedroom around dinner time on April 21 – “about 25 minutes after she said she’d be fine.”